Real life stories from real people

and how our conservation journeys deliver life-changing adventures

We want to ensure that every person who accompanies us on one of our Conservation Experiences has a once in the lifetime trip.

Most of the time their stories and experiences are best told in their own words.

Here are some of those stories, click on the names to read them

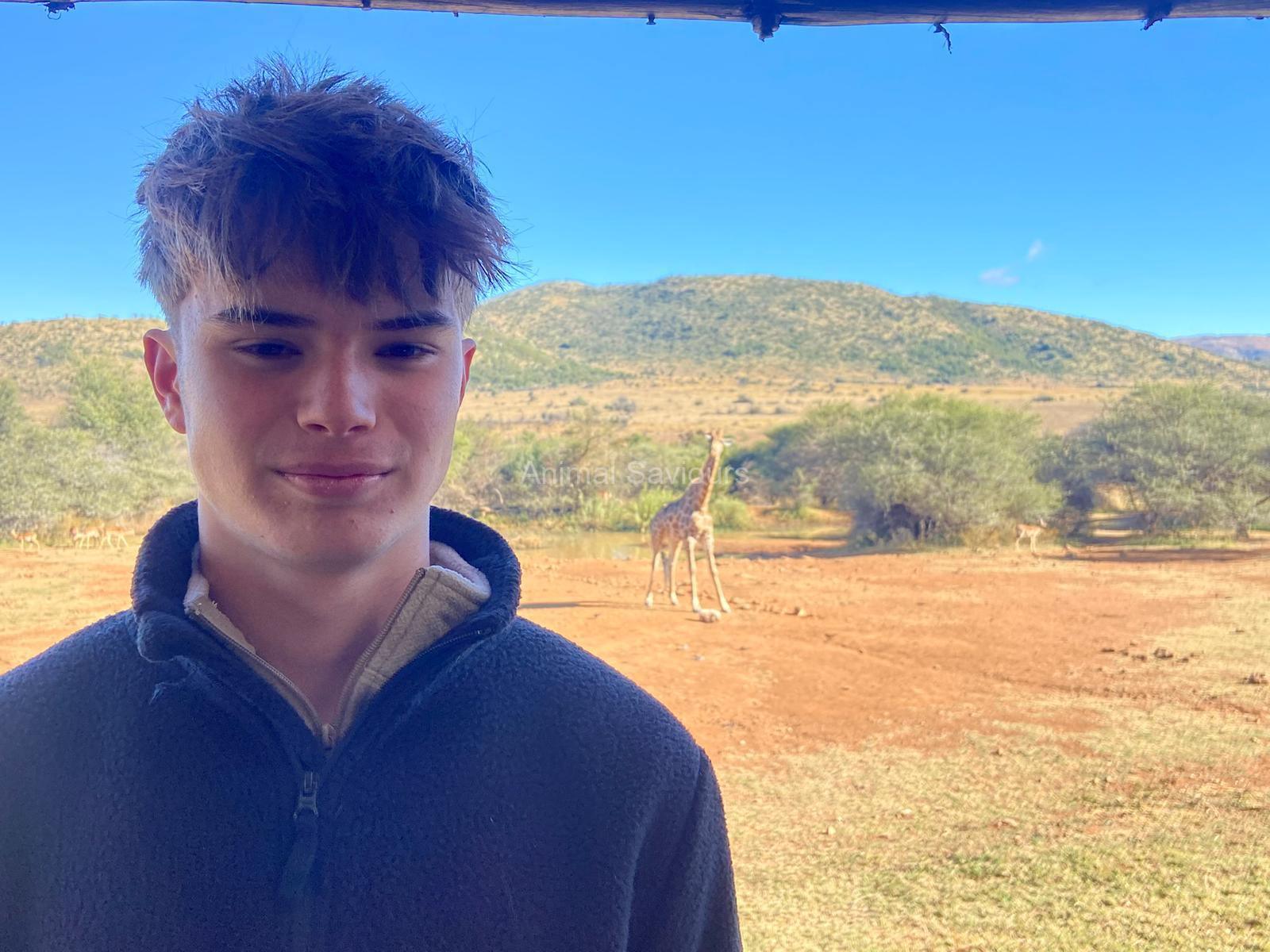

Dan’s Story

Manon’s Photography Journal

Peter’s Birding Adventure

Learn more about the Animal Saviours Conservation Experiences here

College student Dan shares his travel diary from an extraordinary conservation trip to South Africa, joining his father with the Animal Saviours charity. From helping with rhino horn trimming to witnessing Mankwe’s breathtaking wildlife, this is his story of a life-changing adventure.

With my father a vet and trustee for the Animal Saviours charity: a UK based charity that takes volunteers on a unique conservation trip to a field research reserve (Mankwe) in South Africa, I had heard hundreds of fantastic stories about his annual trip. With its captivating wildlife, kind people and amazing scenery, I had been asking him to take me to Mankwe for what felt like an eternity. At the start of this year, he finally asked me if I would like to join him. Well, with such an amazing potential opportunity, I eagerly said yes.

I so was excited to go in June of this year, I was expecting to see and experience something extraordinary, an adventure that would change my life forever.

When I finally arrived in South Africa I was somewhat anxious. My father had told me, as a condition of the trip, that I would have to speak to new adults and help him organise some of the planned activities. This prospect was terrifying, I am not used to talking to groups of adults, especially in a manner of authority. At first, I thought it might possibly be more terrifying than chasing rhino through the African bush. However, I soon came to realise that it wasn’t as bad as I had predicted. The group was very welcoming, and everyone shared a common interest in conservation and stunning wildlife. I quickly settled in with the group.

I cannot put into words how beautiful the reserve is, the staff were very friendly and I must say the food was brilliant; the range of local delicacies, the little shortcut biscuits made fresh every day and the chunky oat bars, called rusks, which you would eat with your tea, they were incredible. Our first activity upon arriving was a game drive. Seeing animals that I had previously only seen on TV documentaries was a surreal experience, it was like being on a different planet all together. My first day ended far too quickly, the sun switched off, disappearing over the horizon after a hard day’s work. The temperature dropped quickly but this was mitigated by our campfire and comforting accommodation.

The days that followed were full of unique activities, starting with setting camera traps at specific points to capture images of target species, including the reserve’s white rhino, buffalo, and nocturnal animals. We then received a lecture about the ecosystem in Mankwe and how they deal with various challenges, including the previous year’s drought. I learned of the complexity in balancing such a delicate ecosystem and the various work undertaken to manage competing species, including the incredible annual burns of various sections of the reserve, this was interesting and played a key role in my understanding of the reserve. Another fantastic opportunity was to see the postmortem exam of a wildebeest. This was truly astonishing, great for biology students, however not the greatest idea if you have a weak stomach. Other activities included using transects to conduct biodiversity assessments, an astrology evening and assessment of differing plant species in the reserve.

The highlight of the trip was most definitely the rhino horn trimming and the translocation of a bull safely to another reserve. The translocation was done to avoid reducing the genetic pool and limit the challenges of having too many male rhinos on the reserve. Whilst of course horn trimming is not what conservationists want to be doing it is known to significantly reduce the risk of illegal poaching and with it the senseless killing of rhinos. I wasn’t sure what to expect, but the horn trimming was surprisingly quick, overseen by a professional approach and a high regard for animal welfare throughout. With the help of reserve staff, the vet in the helicopter and the fast-moving vehicles getting to the rhino in time, the whole activity was so well managed. Being a first responder, arriving at the tranquilised rhinos before the other ground staff, was an unforgettable experience. I was up close with the rhinos, guiding them to the most suitable place for horn trimming to be performed. With the immense weight of the rhino (one was 3 tons!) each one needed at least four people on either side to keep it stable. I needed to concentrate at all times to avoid having my feet squashed!

This trip has made a lifelong impression on me, and I am desperate to go back and learn more. It was exactly how I imagined it and more. I now understand why my father has such a passion for South Africa, and it has no doubt made an imprint on me.

I would like to express huge gratitude to Lynne and the team at Mankwe, to Animal Saviours and, of course, to Miss Jeans and Howells for supporting my time away from school. I would be happy to chat with anybody about my experience and if anyone is keen to explore a life-changing trip, please do reach out with any questions.

Manon’s Photography Journal (October 2024):

Introduction

In October 2024, I had the exceptional opportunity to participate in a Junior Conservation Experience in Mankwe, South Africa for 7 days. Mankwe is a “small” private park of 4700 ha with 28 km of fencing around it. I wanted to learn something about photographing wild animals in safari parks and certainly also the endangered white rhino.

I was mainly interested in the fight for nature conservation, but during my visit my eyes were opened to the living conditions of the people on the ground.

The driving force for my first photo series is therefore the contrasts between rich and poor, between natural beauty and climate change. That is actually the common thread of my thesis: I want to develop myself further in engaged photography. That means that I prefer to make reports with which I can wake people up not to accept everything that happens.

I think we need to take better care of our planet if we want to save the people who live on it. With this series I want to show contrasts between the beautiful nature and the harsh reality of life on site. Unfortunately, there is not a bed of roses everywhere.

I want to show that the lives of animals and the people on the ground are not easy. I want to make viewers aware that things really have to change in the world.

What do I want to achieve with my photos?

This assignment is fascinating but also not so easy. When I decided to choose to make a “reportage” I knew that I would hang part I of my thesis on my short experience in South Africa. There I took a lot of photos of animals, landscapes and street scenes every day. The choice for “reportage” gave me the freedom to discuss images of different themes. So actually there is a story behind every photo, and together those 8 stories form a coherent reportage of my different experiences.

What is my personal motivation?

It makes me angry that not everyone gets the equal opportunities they deserve and that we want to do so little about climate change. My father has worked a lot with people in poor countries and always said to me and my brothers “We are really lucky to be able to live and grow up here in Belgium”. Only now do I understand much better how true those words are.

Now that I have seen such poverty myself, I realize even more how grateful I am to have a safe home, something that is not the case for many families in Africa. But I also understand even better that the animals in nature also suffer from the heat and drought. From the guides there I learned that our biodiversity is threatened. Species are becoming extinct and that has consequences for other species. Until all plants and animals become extinct and then we humans can no longer live either.

How did I go about it?

My original idea was to make a report with images of the wildlife park and to do interviews with participants and staff. When it turned out that I was the only Dutch speaker in the group (all the rest were English and Americans) I decided to drop those interviews.

I did learn a lot of English in Africa, but I still didn’t feel ready to do interviews in English. I did talk a lot with the guides and with the other participants and so I also learned a lot about the operation of the reserve. In the evening in the tent I always talked to my father about what I had seen and experienced that day. But usually I just fell asleep quickly because the days were long.

When I got home I looked at my photos and I didn’t know how I wanted to do it anymore. I then looked up how best to make reports about nature and social themes and in retrospect I should have prepared better and already had a good idea of my story, but I am happy with my first work.

Preparing for the trip

I first collected information about South Africa, through the websites of travel agencies but also the information from the website of foreign affairs. I found most of the info on WIKI. There I read about animals and plants, the climate and biodiversity. I also found it interesting to read about the people. WIKI states that 20.5% of the population has to live on less than 1.25 US dollars a day and just over half live below the national poverty line. That is actually completely unlivable.

Material and equipment

I have usually photographed from a moving vehicle, sometimes on foot. Because it is not allowed to get out of the jeep because of the wild animals, I photographed by hand. I use a telephoto lens (120-400 mm), a 70-300 mm lens, a wide-angle and sometimes a solar filter. Due to the varying conditions, I mainly worked in sports and landscape mode. I also took a tripod, two SD cards (128 and 64 GB), extra batteries and a lens pen with me to remove all the dust. Because it got up to 30 degrees during the day, I always had to be careful that my material was not in full sun.

Technical challenges of my theme

It is full spring in South Africa in October-November so it is very hot from about 9 am. We had to get up very early every day because it got too hot. My equipment should not be too much in the sun and not be shaken too much by the shock of the jeep.

I especially tried to work with these tips:

- Use dramatic light: For example, at sunrise or sunset for an emotional impact.

- Human emotion: Show people who interact with nature and with their living conditions

- Look for contrast: Place pollution or decay next to the beauty of nature to emphasize opposites.

I also tried to take advantage of the very beautiful light in Africa, especially at night. The beautiful lighting is due to the geographical location and the sunlight.

- There is more intense and direct sunlight, especially around the middle of the day. South Africa is close to the equator where the sun is much higher in the sky than in Europe. That’s why I sometimes had to work with a sunscreen.

- Colors appear more vivid because the sunlight has to travel less distance through the atmosphere, so the sunlight is less scattered.

- There are more contrasts and vivid colors because there is much more bright and direct light, the sunlight appears brighter and sharper in tropical areas. There is a shorter but more intense “golden hour” at sunrise and sunset, which provides warm, diffused light that is perfect for photography.

- Dust particles in the air: African landscapes often contain fine dust particles in the atmosphere. These particles give deeper shadows and beautiful contrasts to the landscapes and warm colors.

But due to the presence of heavy industry from mining in that region, the quality of the light sometimes decreased, but still the starry sky at night was much nicer than with us because there is no light pollution.

Common thread : Diverse subjects, one story

My reportage is a selection of different impressions that I gained and that made me think. By that I mean that every photo is a snapshot of things that have stayed with me the most. I could tell more about each theme, but because we have to limit ourselves to 8 photos, I had to make choices for the subjects and images I wanted to show.

I really like nature photography and there are incredible photographers who have specialized in it. They have the means and the time to go out into nature with very expensive cameras and lenses. I’m never going to be able to compete with that… The photos of, for example, Greg Du Toit, Paul Nicklen (the founder of Sea Life) or Cristina “Mitty” Mittermeier are almost too beautiful to look at.

And yet I don’t just want to show the animals. Various topics are discussed in this report. My journey itself is actually the common thread for part I of my thesis. That’s because I couldn’t imagine in advance how each day would go and what I would see. The trips to the village outside the reserve were sometimes very overwhelming. On the streets and at the local market I saw things I had never seen before. I knew then that I wanted to put those things in my reportage as well. That is not to say that I did not find the animals fascinating, because that is certainly not true. But I can’t pretend I haven’t seen those social themes.

The overarching theme of my photo series

My theme is reportage photography: poverty, injustice, climate change and action. I chose this theme: because I am passionate about the climate issue and poverty, as well as the enormous injustice we experience in the world today. Action plays a crucial role, because it is the way we can change. With images I want to capture what is going on and thus help create awareness about these topics.

Why did I choose this theme?

I want to visualize what those problems and situations are. Both good things and less positive things because they help to get things moving. Engaged photography shows problems that everyone knows somewhere but that we ultimately look away from, such as poverty or climate change. That’s because people often think they can’t change anything about it anyway. I think we can reduce poverty and climate problems if we all make a little more effort.

What interests me in photography

What really interests me in photography is how people and the world are connected. You can also see this in my choices of themes such as poverty, inequality and climate. Photography gives me the opportunity to capture these important topics and show the real reality of our world. With a report, I can confront people with the challenges we face, and make them aware of what needs to be done differently.

What is my personal motivation?

My personal motivation stems from everything I have seen and heard so far in my life about injustice in the world. It’s not just about poverty in Africa or war in Gaza or Ukraine, but there are also things closer to home that make me angry. For example, my experiences with a friend who was adopted from China. When I was in Antwerp with her, we were looked at inappropriately and they said “Where do you come from, Chinese?” I don’t think this kind of behavior is normal at all.

It bothers me that people are treated differently, purely because of their origin, like my girlfriend who is not seen as “Belgian”. This also often happens to people of Moroccan origin, for example to police officers, who then want to help others but refuse the help because of prejudice and discrimination. I want to capture reality through photography to show that this behavior is not acceptable and to create awareness about this society.

How do my photos stay cohesive?

I don’t find this easy, but I think the common thread is that the photos should tell a story about what touches me during a trip or a visit. But I’m going to try to stick more to one theme next time. For example, I could have only shown photos of animals, but I thought I had to show other things as well.

Peter’s Birding Adventure (June 2023):

An opportunity arose this year (2023) for me to fulfil a long held ambition to go on a South African safari.

Billed as a Conservation Experience, it was to be based at the private Mankwe Wildlife Reserve, a two and a half hour drive north west of Johannesburg. The taxi ride from the airport raised some concern as I hardly saw any birds and I was struck by the poverty away from the city, with much fly tipping and littering. On arrival though, we passed through a padlocked gate and, after about 10 minutes of sandy track, we were at Waterbuck Camp, our home for the next 10 days. The camp is a collection of chalets, huts and semi-permanent tents, shaded by a group of trees, and situated beside a beautiful lake. The whole is tucked into a rolling landscape of dry grassland with scattered bushes and trees.

As we drew up, we became aware of a chattering and buzzing just above our heads as a crowd of yellow and black Weaver birds were busy building their hanging nests; toing and froing with nesting material. The lake is brilliant for bird watching, being fringed with reeds and largely covered with flowering water lilies.

The Jacana, a beautiful crake, can be seen flying low over its surface, trailing its legs and enormously long toes. They use them to walk nimbly across the lily pads where the more familiar Moorhen has to swim. A piercing yelping alerts one to one of the lake’s resident Fish Eagles, which can be picked out as a splash of white in one of the lakeside trees. The white is his head and chest; the rest is a rich dark brown with chestnut shoulders.

The fringing reeds conceal Squacco, and Green-backed Heron and Little Bittern which, from time to time, reveal themselves by perching prominently or flying. There are a greater variety of Hirundines than you see flying above our lakes, with at least four different Swallow species, a Martin and three sorts of Swift.

Being Spring, it got light at 5:00 a.m. and the dawn chorus is suitably exotic. There’s the yelping of the Fish Eagle; the raucous Korhaans and Spurfowl, both more active at dawn and dusk; the repetitive high pitched Diederik Cuckoo, and the soft carrying call of the Coucal, all backed up by the buzzing Weavers. It invariably drew me out of bed so that most mornings I was there to watch the sun come up.

The Mankwe reserve is about 50 km² of bushveldt, and is home to good numbers of antelope, including Wildebeest, Kudu, Impala, Tsessebe, Eland as well as Giraffes, Zebra, and Ostrich. But it’s the White Rhino which is the key area of conservation. All these and more can be seen on the game drives on the open people carriers.

A feature of the stay was a day trip to the neighbouring Pilanesberg reserve, where there are mega-fauna not present at Mankwe. We saw the rarer Black Rhinoceros and plenty of African Elephants, but I was unsuccessful with Lion, Leopard or Cheetah. At the larger lakes, the heat meant the hippos were staying submerged, revealing only their eyes, nostrils and ears, while a couple of crocodiles basked on the banks.

My bird list was increased by: Sacred Ibis, numerous round the water holes; a single lugubrious Marabou Stork standing out through its size; Kori Bustard, on the grasslands, the largest flying bird; and, a highlight for me, a Secretary Bird, being chased by a Springbok.

Back on the reserve, you see a great variety of birds perched in or on the trees and bushes: Bee-eaters, various larks, Honeyguides, Waxbills, Fork-tailed Drongos or Magpie Shrike. The Lilac-breasted Roller is the most spectacular, with brilliant blue wings when it flies. Coming back in the dusk, Marsh Owls and Nightjars sit on the road and Black Korhaans fly around calling.Game drives are great, but while on the back of a people carrier, it’s difficult to take photos or even use binoculars unless the vehicle is stopped. So bush walks were a bonus way of seeing birds; you hear the calls and you get time to observe them in the air, especially the raptors. There are several Eagles, Yellow-billed Kites, and our Buzzard which they call the Steppe Buzzard, but I didn’t see either of the Vulture species.

I’ve not really done justice to the bird life of Mankwe though, as I saw lots of others including Babblers, Hornbills, Bulbuls and Kingfishers. I identified over 100 species, but there are 380 recorded for the reserve, so I’m hoping I’ll be back…

Learn more about the Animal Saviours Conservation Experiences here